An electro-active polymer hydrogel can be made to “memorize” experiences in the same way as biological neurons do, say researchers at the University of Reading, UK. The team demonstrated this finding by showing that when the hydrogel is configured to play the classic video game Pong, it improves its performance over time. While it would be simplistic to say that the hydrogel truly learns like humans and other sentient beings, the researchers say their study has implications for studies of artificial neural networks. It also raises questions about how “simple” such a system can actually be, if it is capable of such complex behaviour.

Artificial neural networks are machine-learning algorithms that are configured to mimic structures found in biological neural networks (BNNs) such as human brains. While these forms of artificial intelligence (AI) can solve problems through trial and error without being explicitly programmed with pre-defined rules, they are not generally regarded as being adaptive, as BNNs are.

Playing Pong with neurons

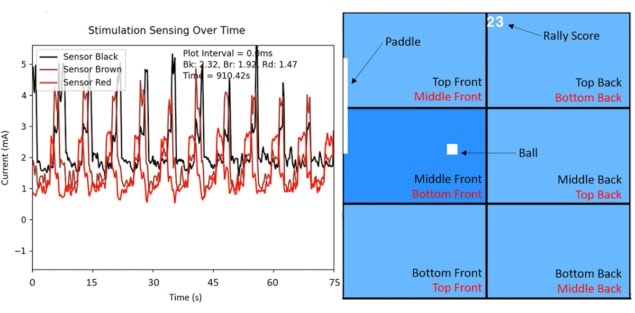

In a previous study, researchers led by neuroscientist Karl Friston of University College London, UK and Brett Kagan of Cortical Labs in Melbourne, Australia, integrated a BNN with computing hardware by growing a large cluster of human neurons on a silicon chip. They then connected this chip to a computer programmed to play a version of Pong, a table-tennis-like game that originally involved a player and the computer bouncing an electronic ball between two computerized paddles. In this case, however, the researchers simplified the game so that there was only a single paddle on one side of the virtual table.

To find out whether this paddle had contacted the ball, Friston, Kagan and colleagues transmitted electrical signals to the neuronal network via the chip. At first, the neurons did not play Pong very well, but over time, they hit the ball more frequently and made more consecutive hits, allowing for longer rallies.

In this earlier work, the researchers described the neurons as being able to “learn” the game thanks to the concept of free energy as defined by Friston in 2010. He argued that neurons endeavour to minimize free energy, and therefore “choose” the option that allows them to do this most efficiently.

An even simpler version

Inspired by this feat and by the technique employed, the Reading researchers wondered whether such an emergent memory function could be generated in media that were even simpler than neurons. For their experiments, they chose to study a hydrogel (a complex polymer that jellifies when hydrated) that contains free-floating ions. These ions make the polymer electroactive, meaning that its behaviour is influenced by an applied electric field. As the ions move, they draw water with them, causing the gel to swell in the area where the electric field is applied.

The time it takes for the hydrogel to swell is much greater than the time it takes to de-swell, explains team member Vincent Strong. “This means there is a form of hysteresis in the ion motion because each consecutive stimulation moves the ions less and less as they gather,” says Strong, a robotics engineer at Reading and the first author of a paper in Cell Reports Physical Science on the new research. “This acts as a form of memory since the result of each stimulation on the ion’s motion is directly influenced by previous stimulations and ion motion.”

This form of memory allows the hydrogel to build up experience about how the ball moves in Pong, and thus to move its paddle with greater accuracy, he tells Physics World. “The ions within the gel move in a way that maps a memory of the ball’s motion not just at any given point in time but over the course of the entire game.”

The researchers argue that their hydrogel represents a different type of “intelligence”, and one that could be used to develop algorithms that are simpler than existing AI algorithms, most of which are derived from neural networks.

Experts debate the possible paths to human-like AI

“We see this work as an example of how a much simpler system, in the form of an electro-active polymer hydrogel, can perform similar complex tasks to biological neural networks,” Strong says. “We hope to apply this as a stepping stone to finding the minimum system required for such tasks that require memory and improvement over time, looking both into other active materials and tasks that could provide further insight.

“We’ve shown that memory is emergent within the hydrogels, but the next step is to see whether we can also show specifically that learning is occurring.”